26 Aug Canadian BMX Company History: Kostya Chimkovitch & Crimson Bikes (2013 to 2018)

Earlier this year, ahead of the 2021 re-launch of the site, my close friend, Kostya Chimkovitch expressed interest in contributing to the Northern Embassy. We started brainstorming project ideas together and eventually a concept came to fruition: What if someone were to document the history of Canadian BMX companies? As a machinist by vocation, Kostya has a strong background in manufacturing. He also ran a small BMX frame and component company with his friend and then-business partner, Brian Kelly from 2013 to 2018. It was clear Kostya would be the perfect candidate to share some stories about past and present BMX companies in Canada. To kick off Kostya’s ambitious history project, I’d like to introduce you to the man himself. Read on to learn about Kostya’s history in BMX, experiences in manufacturing, and life off the bike.

Documenting the history of Canadian BMX companies is no easy task. What motivated you to take this on?

Ask your average Canadian rider to name a Canadian BMX company; chances are your answers will be split between MacNeil and blank stares. There is a lot of history of people running Canadian BMX companies. It seems a shame for all those stories to be lost in the passing of time.

For the sake of this project, how do you define a “Canadian BMX company?” What are your parameters?

The owner/entrepreneur is from Canada, and the company has at least one physical BMX part in its line-up (not clothing items – that list would be too long for me to handle).

What are you doing behind the scenes to work on this project and what will it look like when it’s done?

It started with a brainstormed list of companies, along with a list of generic, open-ended questions that I would like each company owner to answer. Since then, I’ve been sleuthing for people’s names and contact info (nothing nefarious, just Google and Instagram searches), and reaching out to them. Once done, I hope to have talked to everyone who is or was involved in making BMX hardgoods in Canada over the last 30 years. Initially, I was thinking of doing a single article, but after realizing how much history there is to cover, I opted for a series of articles.

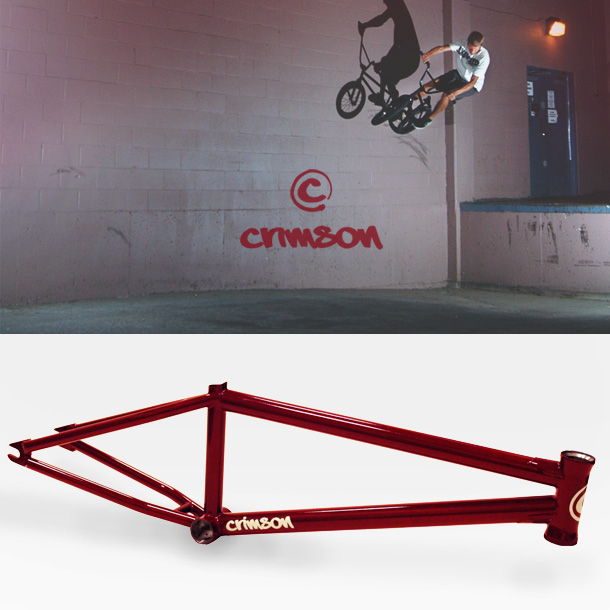

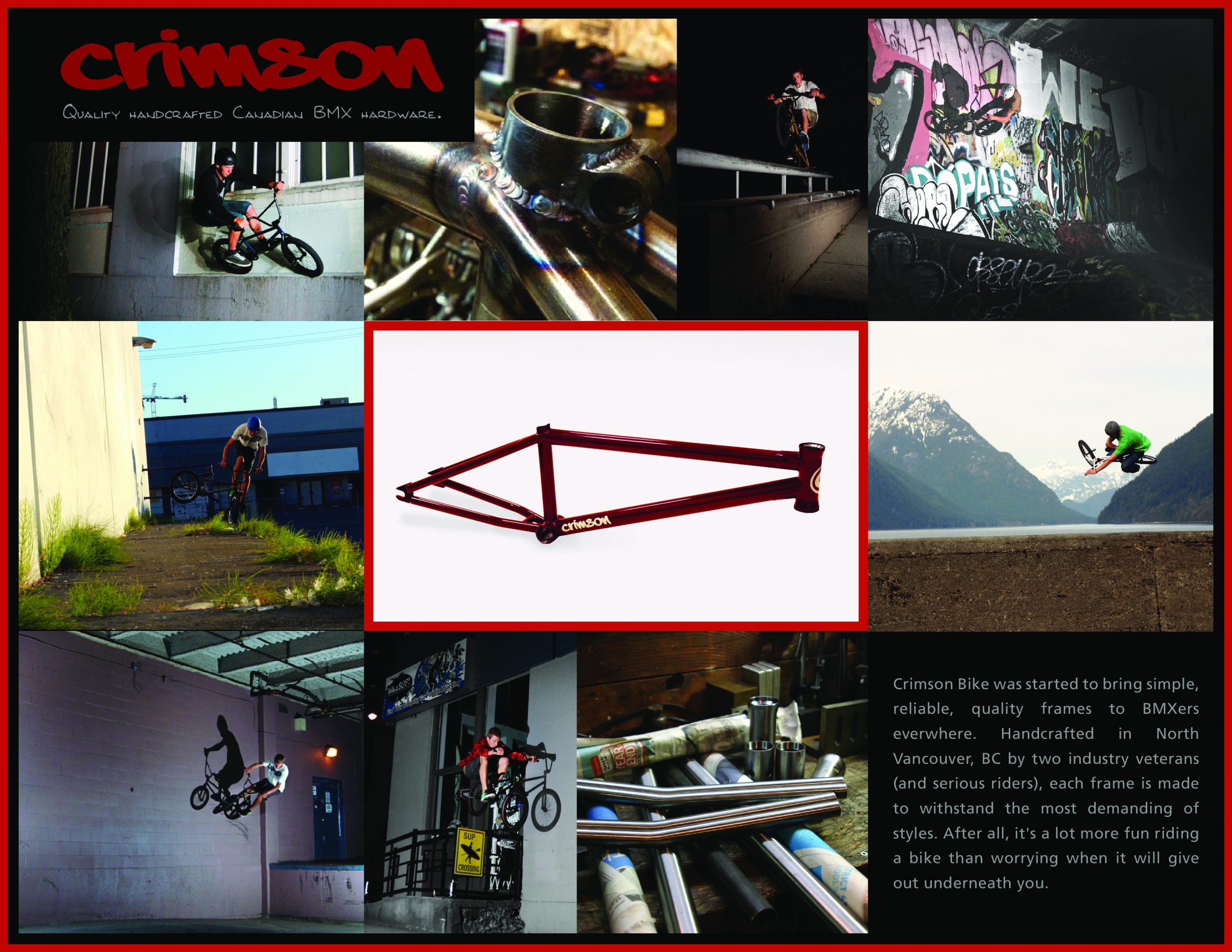

You’re no stranger to manufacturing BMX components in Canada. Can you talk about Crimson Bikes? How did you come to enter the hardgoods business?

I’m a machinist by vocation, and have been around bikes since I was 6 years old. I don’t think I’d have entered that trade had it not been for bikes and my curiosity of how bike components were made. Throughout my career, I’ve always seemed to gravitate towards bike-related work: a stint at Race Face, a couple of years up in Whistler with North Shore Billet, etc. I was also watching other friends of mine working on things like Critical BMX and Chromag, all of which definitely showed me I could make whatever I wanted if I set my mind to it. Plus, I’ve always took a specific joy in using something I had a hand in designing or manufacturing. So it was basically a natural progression to try and build on that using my own ideas.

I also reconnected with a guy named Brian Kelly in 2012. He was my mentor and the chief designer at Cove Bikes back when I was a 16 year old grom mechanic there. Brian took up welding and frame building while nursing a shattered knee. One thing led to another, and we collaborated on a one-off BMX frame for me to beat the crap out of.

Sorry for all the mountain bike references by the way. I was getting ridiculed for riding mountain bikes at the skatepark well before I ever touched a BMX. I was also riding mountain bikes before they became a retirement tool for professional BMXers.

2000. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

2000. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

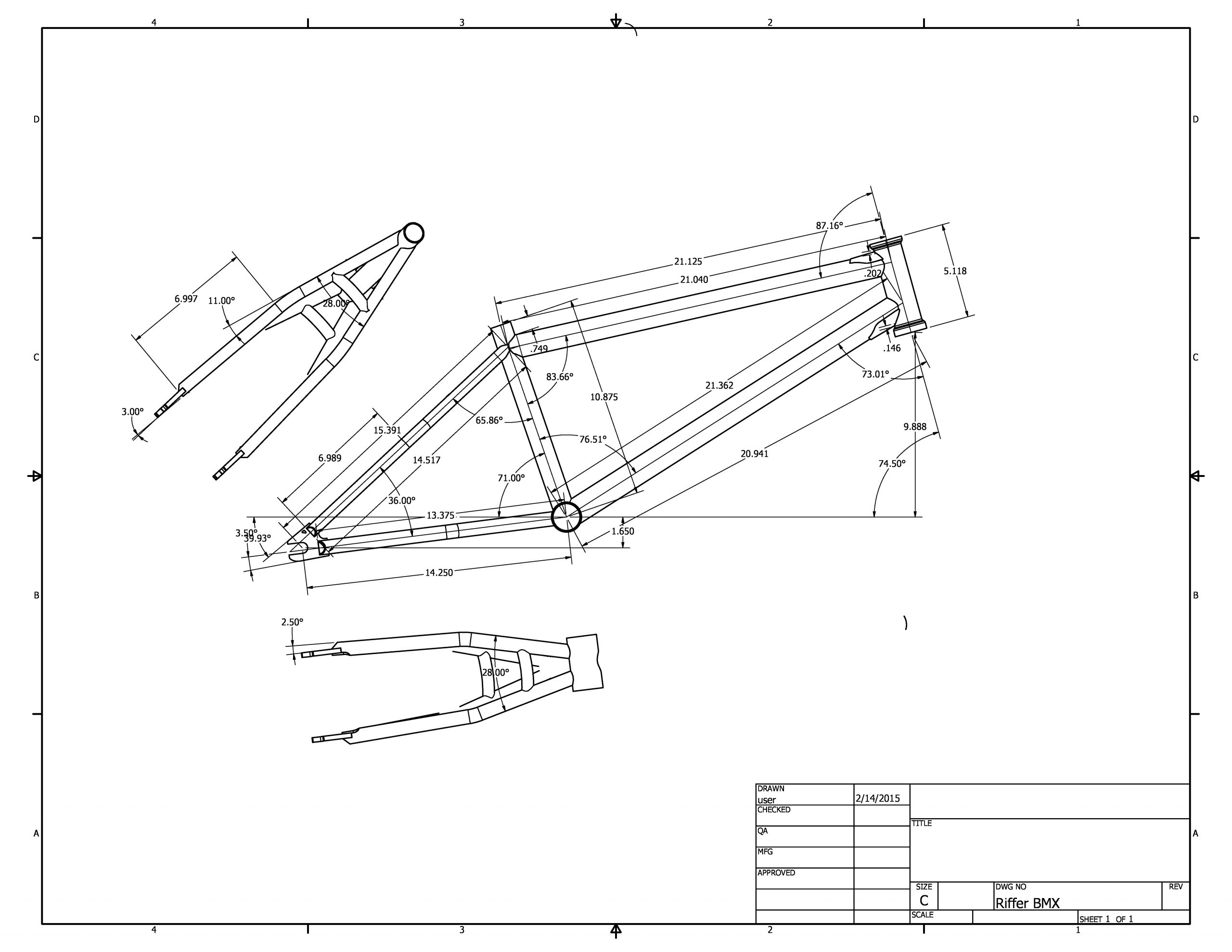

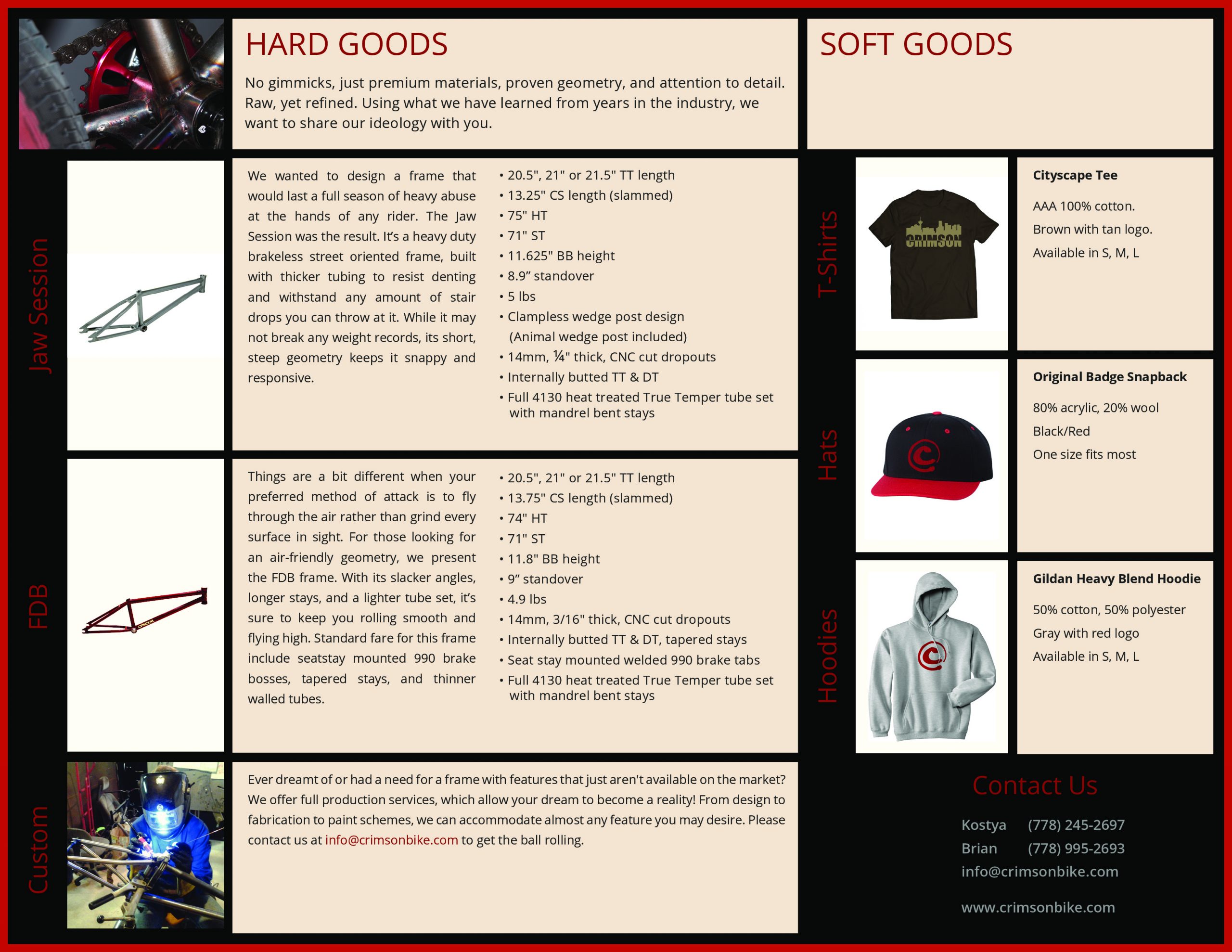

Throughout Crimson’s lifespan, what products did you and your partner manufacture?

We made a bunch of frames (of all kinds, not just BMX), and a run of stems.

2013. Brian and Kostya. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

2013. Brian and Kostya. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

What were some of the challenges to manufacturing in Canada?

Getting materials up here was definitely problematic. We weren’t ever big enough to place orders with an overseas supplier. We relied on places like Solid, Paragon Machine Works, Henry James, and sometimes plain old Aircraft Spruce to get materials. A lot of time was spent figuring out how we can use full lengths of tubing and form/machine it to what we needed, rather than buying bicycle-specific tubesets. This was both for cost and availability reasons.

When would you say the brand was at its peak? What signified that peak to you?

Crimson was so small and so much work that I never felt like we could take a step back and rest on our laurels. They simply weren’t there to rest on.

We had a few shredders ride our frames though. Andy McGrath got a frame after Ryan Taylor purchased it for him through Riffs. We gave a frame to Travis Sexsmith; he rode it and didn’t break it for at least a couple of years. That was nice.

Honestly, I think the peak of Crimson to me was when I was sitting at the computer in the shop after a weekend on the CNC mill, shifting my gaze from the stem design on the screen to the physical prototype in my hand. I felt a sense of accomplishment and finality right there and then. Nowadays, I feel somewhat similar when my friends are lined up on the deck at Confederation Park and all of them are still rocking the Crimson stems.

How would you characterize the brand’s decline? What did that look like and what caused you to finally cease operations?

There wasn’t really a drastic end to it all. In fact, should Brian and I choose to, we could head right back into production tomorrow. However, I think both of us are completely over it at this point. The ratio of work vs. reward is simply not for us. I like riding bikes as much as making them. With a full-time job and family commitments, something had to give. As for Brian, he took over the shop space and now runs a machining/fabrication business out of there; he can’t afford to spend 60 hours a month working on a few frames that will sell for less than $700. As for how we got there? Eventually we both just ran out of steam. It was physically exhausting, mentally draining, and financially stupid. Neither of us are good businessmen and it showed.

In hindsight, is there anything you wished you had done differently while the company was operational?

Grown thicker skin sooner. I was naïve and thought that there would be more appreciation for what we were trying to do. While a lot of the responses to our work were positive, it definitely was not universal. There wasn’t much in the way of open negativity, but a strong feeling of apathy. I was so excited to be contributing to Canadian BMX in my own small way by doing something I thought was kind of cool, and it felt like there were a lot of shoulder shrugs in response. I’m not trying to say anyone owed me anything, but we were handcrafting BMX frames in Vancouver. It isn’t exactly an ordinary occurrence, you know? So when that’s met with cricket chirps, or worse yet, credibility checks, it can really get to you. It certainly got to me, though it shouldn’t have. With that said, thank you to anyone that did support Crimson when it was around.

Do you feel any of your ideas/designs resonated within the BMX industry moving forward?

My only contact as Crimson with the industry consisted of John Povah leaving a comment on Instagram under one of our stem pictures accusing us of stealing Terrible One’s Cyclops stem wedge design. I’m sorry John; that’s just the way the timeline worked out. I’m sure Joe Rich managed to survive through someone in another country releasing 25 stems with a somewhat similar wedge design and completely different geometry, a year after the Cyclops stem dropped. I would also argue our wedge design was a bit better since it didn’t get stuck and didn’t require a mallet to disassemble.

What advice or warning would you give to someone who is considering starting their own Canadian BMX company?

I am going to sound somewhat bitter, but it’s all about who you know. I spent the majority of my riding “career” as a total recluse, and when I started coming around talking about the frames we were making, a lot of people went “who the hell is this guy?” Also, be prepared for jealousy and cold shoulders from a community that can’t stop touting how it’s all one big family. It will feel very two-faced. You will need to have your game face on, along with a clear vision for success. I failed on both those fronts repeatedly, and it chewed me up and spat me out. If you can brace yourself for that, just go for it. Don’t overthink it. At the end of the day, you can just walk away.

2015. Burnaby, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Andrey Chimkovitch.

2015. Burnaby, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Andrey Chimkovitch.

2015. Riders Union Ramp. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2015. Riders Union Ramp. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

Shifting gears, I want to get into some personal questions. You’re originally from Belarus. What was life like as a kid in a former Soviet Bloc country?

It was the best of times because I was young and had no idea what was going on around me. I got to run around high rise rooftops and abandoned factories from the age of 5. The entire neighbourhood was our playground, and the only limit was what you were caught doing.

I got my first bike at the age of 6. It had 5 gears, lever brakes (no kickback hub nonsense) and 20” knobby tires. I rode that thing into the ground, and eventually it fell apart. From there, I was bikeless up until we got to Canada.

1996. No socks, no shoes, no potatoes. Minsk, Belarus.

1996. No socks, no shoes, no potatoes. Minsk, Belarus.

Can you tell that story about being super hydrated when you were a kid in Belarus?

Hahaha shit. Every summer we’d spend a few weeks in a rural countryside village, living at a family friend’s farm. One time, my parents had to go back to the city and left me in the village with my grandma to kind of look after me. I asked to go outside and play and she said yes. So, bored on my own with no kids to play with, I decided to go exploring and walk the dusty dirt road about 3 km to the next village over. I am 8 years old, it is mid summer, and I have no water or anything else to sustain myself on my 4 hour adventure in the scorching sun. I got to the neighboring village, climbed an apple tree and ate a few apples, then decided to head back. When I got to the home village, I realized I was feeling quite hot and clammy, and that I was really thirsty; so much so that I stopped at another farm and asked for some water. The farmer dropped a bucket into his well and pulled it out full. I literally chugged it all on the spot; it must have been about 5 liters. I didn’t feel any better, and at this point I’m getting weak and dizzy. I barely made it to the farm we were staying at, and collapsed into bed to my grandma freaking out. I was bedridden for 3 days with a very memorable fever. 0/10, would not recommend.

Is there a BMX scene in Belarus? If so, what’s it like?

When I lived there? Hell no. Bikes were a luxury and a mode of transportation. Nowadays? I have only been back once and did not run into any riders while there. I’ve seen enough on the Internet to say that there are at least a few riders around though. Stress BMX did a road trip to Minsk, and the edit bangers were all filmed on a ledge that I used to see from my old bedroom window.

What motivated your family to move to Canada?

Won’t somebody think of the children! It was for me and my brother: a better life for the kids. Looking at what’s been going on over there this last year, I’d say my parents made the right choice. Thank you.

How did you adjust to life in Canada? What was that transition like?

I was the weird kid who didn’t speak any English, thrust into grade 5 in a public school. It was exactly as you might imagine that going. Thankfully, the school was in an area that was heavily populated with new immigrants so I didn’t stand out too much. Obviously, the culture differences were huge, and took us (especially my parents) quite some time to fully adjust to. One example is something as simple as smiling at people in the street: over there, it is simply not done. In fact, it is viewed as a sign of stupidity and weakness to be smiling without any apparent reason. I got a quick lesson in that when I went back to Belarus a couple years ago. Also, people in Canada care. Be it someone checking in on you when you fall off your bike, or the police wondering what you are up to; people care and check on you. No abandoned factory exploration here in Canada (at least not as readily as back in Belarus). It all worked out in the end though.

You started out riding mountain bikes and later found BMX. Can you talk about your discovery and/or transition periods in these two disciplines of bike riding?

My parents were awesome enough to get me a bike within a month of arriving in Canada. It was a Toys-R-Us pile of shit, and I promptly destroyed it by jumping curbs and dirt mounds. Luckily, I have always had a bit of a scavenger streak in me, and quickly amassed a fleet of bikes I had found next to dumpsters in our neighborhood. All of them were older mountain bikes. I started to notice similarities between them and the fancy bikes with shocks (lucky!) that I was seeing in the windows of the local bike shop. Once we moved to North Vancouver, I discovered this new underground movement called “north shore freeride.” I was instantly hooked. Skinny log rides up in the air, wheelie drops to flat, slow crawls down rock faces; I spent most of my free time attempting to master all the obstacles on whatever trails I could find.

A fresh new skatepark called Parkgate was also built during my first summer in North Vancouver, so I spent some time there too, getting yelled at by adults and getting into fights with kids on skateboards. I knew BMX existed, but I really wasn’t bothered to try it out until my brother got on one. His testimony to how fun it was pushed me to finally get one at around 16 years old. As soon as I learned to deal with the twitchy smaller wheelbase, I was hooked. I basically stopped mountain biking overnight and didn’t touch a big bike until I moved to Whistler at 21 years old. Now, I try to maintain a healthy balance in my bike choice.

2000. Parkgate Skatepark. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

2000. Parkgate Skatepark. North Vancouver, British Columbia.

Aside from the last few years, you’ve spent much of your late childhood and early adulthood living in North Vancouver. I can only imagine how different that city looks and feels since you first moved here. What’s it like seeing the cityscape and environment change during this seemingly endless construction and real estate boom?

In my eyes, it’s been fucking wack. No word mincing necessary. The North Vancouver I grew up in and cherished is long gone. The serenity of the woods I used to ride in is no longer there. The feeling of a quiet hillside community full of nooks and crannies is diminishing with every densifying high-rise. Don’t get me wrong – it’s still an incredible place and I know that I sound like a salty gatekeeping jackass, but for me it’s impossible to reconcile what it used to be with what it has become.

2015 Crimson Bikes Promo featuring Kostya and Andrey Chimkovitch.

Can you tell the story about how you became friends with Slade Scherer? When Slade was living in the Lower Mainland, you two were basically inseparable.

Like I mentioned earlier, I tend to be quite reclusive when riding. For about 5 years, I basically rode on my own or with my brother Andrey and our friend Jason Reimann. Around 2015, Andrey developed a debilitating knee issue that basically ended his BMX days. Jason had moved up North for work a couple years prior. All of a sudden, I was always riding alone.

After about a year of riding on my own, I joined the Vancouver BMX Facebook group (thanks Lucas Lundy for holding the scene together even after you moved out of town). In the winter of 2016, we were playing an online video clip game of BIKE – something like 25 people started on it. The idea was to have someone set a trick and film it, and for everyone else to have a week to film themselves doing the same trick. The game went on until it was down to Slade and I about 3 months later. We kept going trick for trick with no letters accumulating until he pulled a back rail icepick at Gorilla Jam. I was about to go to Barcelona and all comparable setups around town were way out of my league. I took the letter. After the first couple of days in Barcelona, I got word that Slade broke his face at Kush [trails] and was throwing in the towel. Naturally, I couldn’t accept a win by default so we both agreed to call it a tie and a game well played.

Once I got back from Spain, I ran into Slade at Hastings [skatepark]. We ended up chatting a bit and he offered me a seat in his van for the annual No Bikes trip. Slade and I clicked right away – our motivation levels are very similar, we tend to enjoy the same style of spots and parks. It just works. Once we got back from the trip, we shared basically everything riding related – from park sessions, to street missions, to DIY builds. He’s one of the few BMXers I know that will get up at 5 AM to go build a DIY spot, and follow it up with a bowl rip right after.

Slade moved back to Kelowna so we don’t get to hang as often, but he’s a lifelong friend for sure.

2017. Barcelona, Spain. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2017. Barcelona, Spain. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

No Bikes 2018. Kostya and Slade. Montana. Photo Credit: Cary Lorenz.

No Bikes 2018. Kostya and Slade. Montana. Photo Credit: Cary Lorenz.

Can you share one story that really sums up Slade?

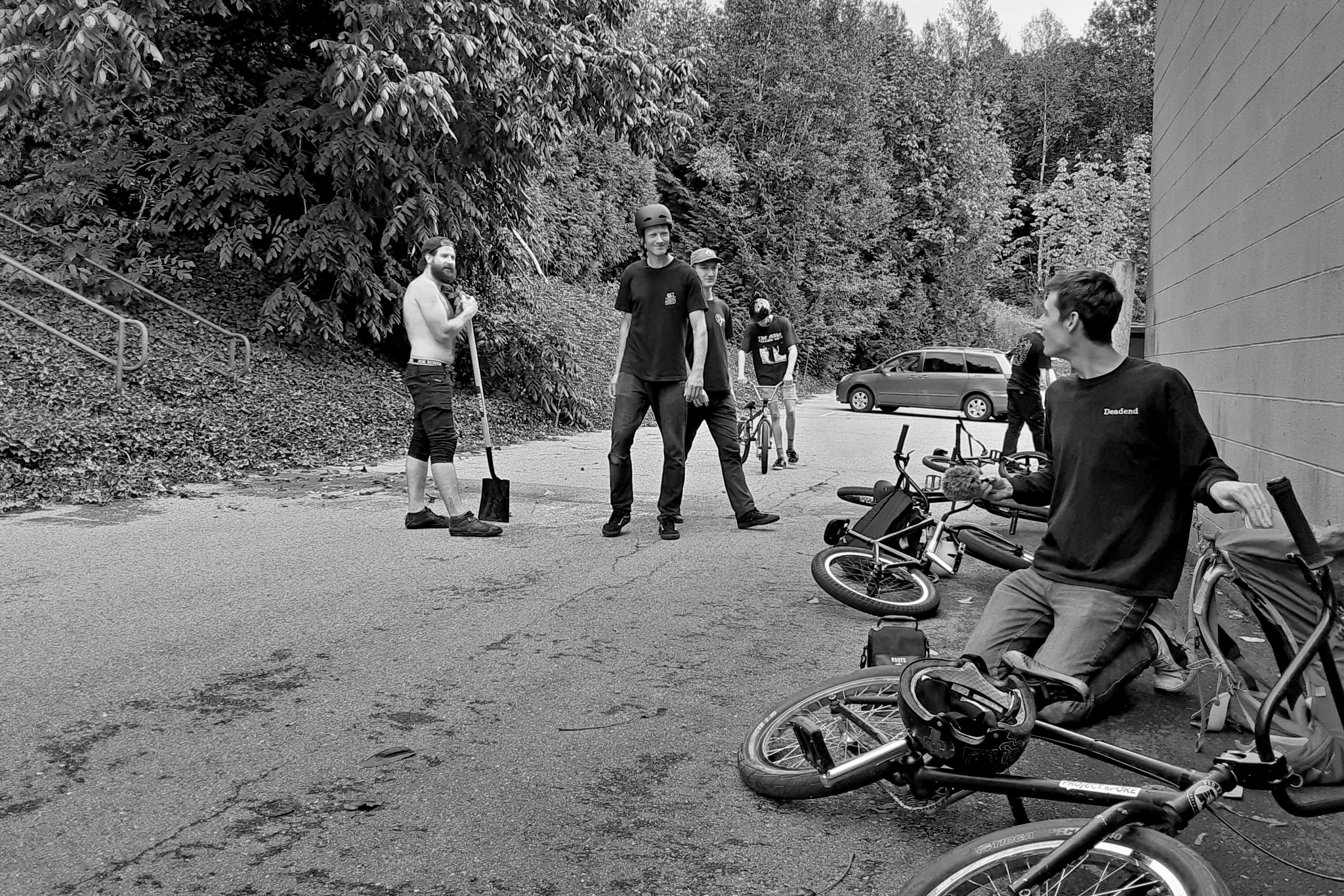

In 2018, our friend John Thompson organized the Confederation Park Old Man Jam. Slade had the idea to build a moveable wallride/bank set-up and of course I agreed to help. We were going to do it under the cover of darkness right at the park. So we were hanging out, casually riding, and waiting for the sun to go down. The other park users were your usual mix of skaters and scooter kids, except for this one kid on a BMX bike that neither of us had seen before. He was serious about it and had some moves. Naturally, Slade starts chatting with him, finds out he’s 17 years old and his name is Eamon McCaffrey. He just moved to Vancouver. Next thing I know, it’s dark and Eamon is getting in the van with us to go shralp some recycled construction wood from a nearby site. He hung out and helped us build until 1 AM that night. That to me is Slade in a nutshell – from total strangers to “get in the van, we’re doing some dumb shit and you’re gonna love it.” We are all still friends to this day too.

2019. Left to right: Eamon McCaffrey, Kostya Chimkovitch, Slade Scherer. Squamish, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Derek Bolz.

2019. Left to right: Eamon McCaffrey, Kostya Chimkovitch, Slade Scherer. Squamish, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Derek Bolz.

2020. Left to right: Slade Scherer, Kostya Chimkovitch, Eamon McCaffrey, Joel Sittler, Justin Schwanke. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Thomas Henderson.

2020. Left to right: Slade Scherer, Kostya Chimkovitch, Eamon McCaffrey, Joel Sittler, Justin Schwanke. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Thomas Henderson.

You spend a lot of time in the backcountry hiking, skiing, snowshoeing, etc. How did you get into that? Do you have the same level of passion for those sports as you do BMX?

I definitely enjoy my time in the outdoors, but it’s less about “sport” and more about “adventure” now. I’m not trying to get any Strava KOM’s or climb every peak in the coastal mountains; I just want to have some quiet time in the woods. If that comes with an awesome view or a few pow turns on the way down, all the better. I need time to recharge myself, and it has become next to impossible to find the space to do so without really getting far out there. I’ve been getting more into it over the last couple of years as I feel less and less able to ride BMX at the same level I used to. I guess it’s a bit of a BMX retirement plan for me; I didn’t want to be left with nothing to do once it winds down.

Can you share a story or two about some close calls or dangerous situations you’ve encountered in the backcountry?

I like to think I’m a fairly calculated risk taker when it comes to my outdoor adventures, mostly because I usually end up doing them all alone. Mother nature could give a fuck about you; she will eat you up and belch your bones up 3 years later if you’re not careful, and I respect that. So I don’t have any overly wild backcountry stories… but let’s see…

I almost slipped off the West Lion when I attempted to scramble it on my snowy day thru-hike of the Howe Sound Crest Trail. Too much snowpack melt dripping onto an already precarious route. Bad idea, shouldn’t have been attempted. I got lost snowshoeing in the mid-mountain woods of Mount Seymour. It wasn’t too far from the parking lot, but it was still an unpleasant feeling overall. I nearly got frostbite skiing out to Elphin Lakes this winter. Apparently I lack circulation in my extremities, namely my fingers. I’m now a converted mitten man. I turned back from a scramble in Manning Park after starting a 300 foot rock slide with a single misstep. I needed to sit down and regain composure after that one.

How does BMX fit into your life these days? On a given week, how much riding are you doing and what do the sessions look like?

BMX hurts. Plain and simple. Most of the time I feel good until I get on the 20.” So my riding intensity and terrain choice is largely driven by how I’m feeling. If it’s transition, I can do it 3 or 4 times in a week. If it’s a casual street mission, I can do 2 or 3 of those. If it’s a spot hammerfest, I’ll have to lay low for about a week after to let my joints recover.

2014. Portland, Oregon. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2014. Portland, Oregon. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2021. Chilliwack, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2021. Chilliwack, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

We’ve spent plenty of time together filming for the next Weird & Revered full-length video and you’re well on your way to having a full part. What gets you excited about the filming process, both behind the lens and in front of the lens?

It’s just a documentation of good times with great people. As corny as it sounds, I hope to look through this stuff when I’m way older and remember it as it happened. Plus, like I said, I spent most of my earlier riding years being a total recluse. There is a selfish joy in seeing people stoked on something you pulled, and this is the first time in my life I’ve experienced that. Lastly, new spots and new ways to look at old spots is great.

2020. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2020. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2021. Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2021. Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2019. “Team Dad & Friends” section from the Weird & Revered DVD, Vagabond Squad. Kostya footage @ 5:48.

With our discussion on Crimson, you alluded to your experience as a machinist. BMX and passion projects aside though, what’s your real day job look like?

I’m trained as a CNC machinist. Basically I take rough material blanks, and using cutting tools and processes, turn them into finished parts as per the customer’s blueprints. I have recently moved into the role of production manager which has been a blessing and a curse. There really isn’t a typical day for me; I always seem to be putting out fires and dealing with issues. I spend a lot of time on the computer writing emails, chasing stuff down, and making sure the shop runs as smoothly as possible. All this means is I am very rarely on the machines anymore, at least professionally. I can still throw down and make it happen, but the opportunity never really presents itself. I do the occasional personal project after hours just to remind myself that I still can.

All things said, you’re a pretty well-rounded adult by traditional standards. You take your career seriously, you’re a new homeowner, you’re in a long term relationship, you prioritize time with family, and you always seem to be there for your friends. I hear you throw around the expression, “Peter Panning” every now and then. Can you talk about this tension you face between embracing youth and taking on more responsibility?

It ends up being a double edged sword. On the one hand, as I get older, there are times I find myself wondering if riding is worth it: the hurting, the stress, the disappointed looks. Recently, I did some damage to my legs trying something that was, in retrospect, clearly above my pay grade. I had to hobble around with a cane, completely debilitated. A 14 year old kid at my work saw the video clip of the crash and his immediate response was, “Why? What did you think was gonna happen?” That got to me a bit… Was it worth it? I’m 33 years old now, having my life choices questioned by someone half my age. I got off easy too; the outcome could have been way worse. I could have been in the hospital. Defaulting on mortgage payments due to a crash would not have felt good. Not to mention that now I am sidelined for the foreseeable future waiting for a bunch of tendons to heal.

On the other hand, sometimes I will be cruising down a street and get hit with the realization that I pedaled down the same street, holding my bars the same way and looking for the same things, only it was 15 years ago. And that makes me think, “I can do this for another 15 years, easy.” Bikes have helped me through some rough times, and I can’t just turn my back on that. Silly or not, there’s nothing that makes me feel quite the way a BMX does.

I guess in the end, I’m still trying to strike a balance: to be able to hold on to that cherished feeling of freedom while accepting that I’m in a different spot from when I started riding, both physically and mentally. We all grow and evolve as we get older. I have no interest in trying to act like I’m still 16 at this point in my life, but I also want to hold on to the fun bits. The more I think about it, the more it seems the answer is to just have fun and not take it too seriously.

2013. Youthful battle wounds.

2013. Youthful battle wounds.

2018. West Kelowna, British Columbia. Photo Credit: John Thompson.

We should probably wrap this up; I know I could keep asking you questions forever. I’m excited to see the articles drop for your “History of Canadian BMX Companies” project. Thanks for taking this on. Any last words or shout-outs?

Mental health is all the rage nowadays. Everyone is talking about it. Good. Keep it that way. Check in on your people. Make sure you take the time to make yourself okay. That shit is important and nobody has to suffer in silence as long as they have good friends around them. Do your part. That’s my public service announcement.

Thanks? I definitely have those. Christy, my much better half. She learned early on what it means to be involved with a BMXer and has stuck by me regardless. I’m lucky and I know it. My parents and my brother: you are family. Enough said. My friends. I don’t want to list them for fear of leaving someone out. I have been lucky on this front in the last few years too; seems I meet more great people now than I had in my entire previous life. All the crews: No Bikes, Weird & Revered, On Some Sugar, Back Alley BMX, Crank Industries… It’s all just dudes riding little kids bikes. Thank you all for keeping it fun.

2020. Left to right: Slade Scherer, Kostya Chimkovitch, Matt Thomson, Eamon McCaffrey. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2020. Left to right: Slade Scherer, Kostya Chimkovitch, Matt Thomson, Eamon McCaffrey. Abbotsford, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Justin Schwanke.

2019. Soldotna, Alaska. Photo Credit: Aaron Gates.

2019. Soldotna, Alaska. Photo Credit: Aaron Gates.

2016. West Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2016. West Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2020. Waimea, Hawaii. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.

2020. Waimea, Hawaii. Photo Credit: Christy Charlesworth.