22 May 43 Years of BMX – An Interview with Wade Nelson

With 43 years of BMX riding comes 43 years of reflection. We have a special interview today featuring Wade Nelson. From starting riding in the burgeoning 1980s to progressing through the commercially low period of BMX in the early 1990s to working industry jobs in the late 1990s to transitioning into a career in teaching in the 2000s, Wade has plenty of stories about his life on and off the bike. Aaron Gates and I teamed up for questions on this one, and we’re appreciative of the amount of wisdom Wade had to share. Dive in for an extensive interview with one of Canada’s most “seasoned” bicycle stunt riders.

Justin: Let’s start with a general overview of your time on two wheels. Can you share a bit about your involvement and history in BMX?

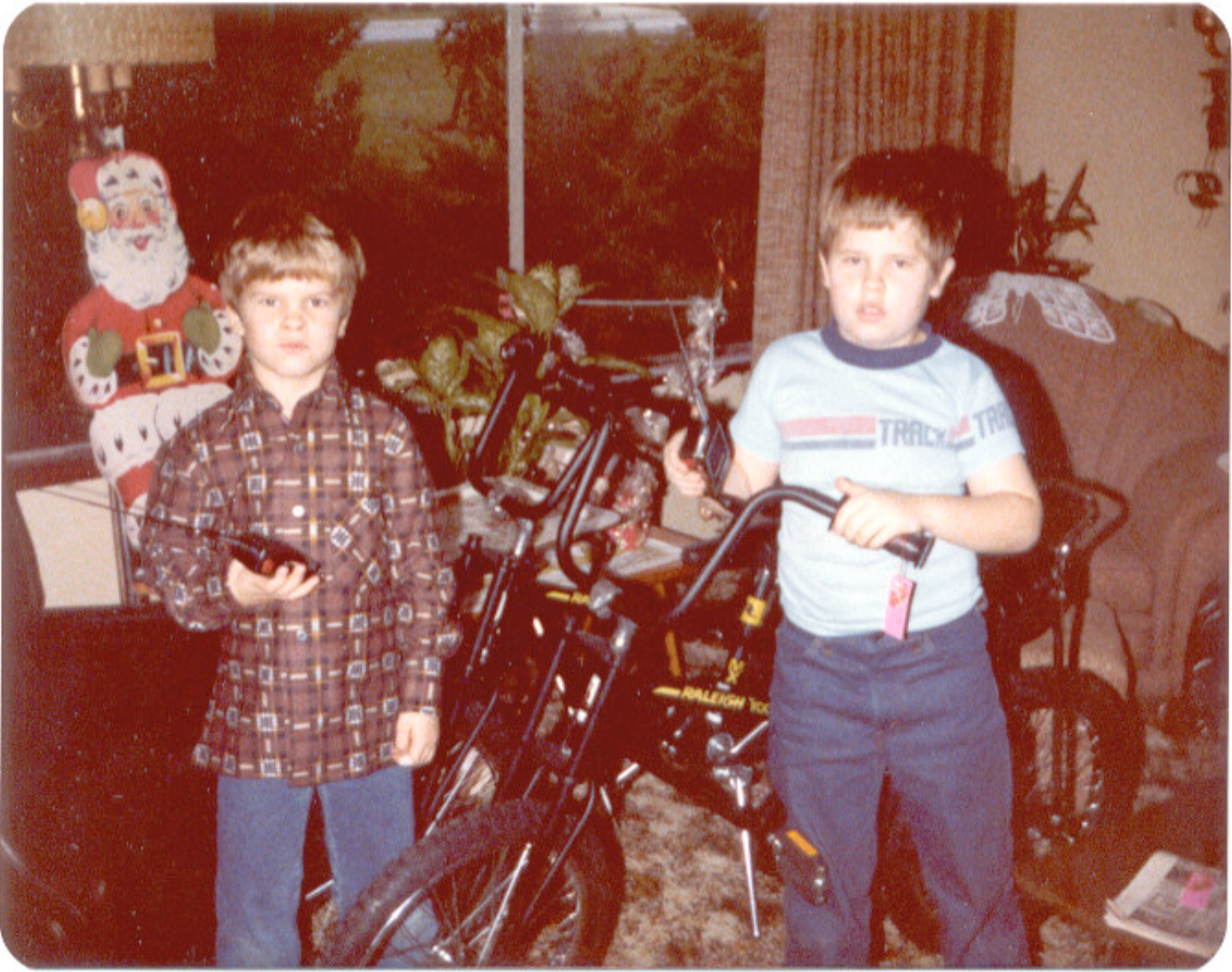

My first proper BMX bike was a Xmas gift in 1980. I have a picture of my brother Scott and I standing in front of our new bikes while holding walkie-talkies with Xmas decorations behind us. So, BMXmas. I was nine years old. In about 1982 I had my second Raleigh BMX bike, a Supercross, with blue anodized parts and my first freewheel. In 1984, my mother received the proceeds from the sale of some property and I got a used PK Ripper for about $350. That was stolen. The replacement bike was a Hutch Pro Racer, and this one was built with Freestyle parts – specifically, a stem with a Potts’ Mod (cable routed through the stem bolt) and a front brake.

Two years later, in the summer of 1987 (back on a coaster brake), I entered my first Freestyle contest in Victoria, BC at 16 years old. The most important part of that first event wasn’t the competition – it was meeting other riders. I met so many important people that day including Darren Wong, Alan Brand, Mel Gooder, Ron Mercer, Rob Dodds, and Jason Hollister. They were all experts, while I entered novice.

Three years later, I turned Pro for flatland after having won 18 and over Expert five times in less than a year. I am pretty sure that I have the first solo part in a Canadian BMX video in Jason Brown’s Canadians Eh (1990). I peaked as a flatlander in 1990. I started over as a mini-ramp rider and worked my way back up to Expert (Stunt Boy at the 1995 Daytona Beach BS Contest) by 1995. I probably peaked as a ramp rider by 1997. My last “real” contest was 2005, when Maxime Vincent brought me out of retirement to join him in a team version of PIG / SKATE / that we did in Trois Rivieres, PQ called “KOQ” or King of Quebec. He carried me, but we won. So that was sort of a Pro win.

Oh – I entered the Five-Clip Fever Northern Embassy contest in 2015. I think that I got an honourable mention or something.

And come to think of it – I entered an online contest for some We The People Utopia bars recently – and again got honourable mention.

I was at the first two X Games. I worked for Airwalk in the summer of 1996. I was a substitute TM for GT at two BS contests in 1997. I managed the Rewind Clothing BMX team from 1996 – 1999. I worked for SST / Brian Scura (inventor of the Gyro) on and off from 1997 – 2002 (and lived in California for six months working for the company in 2000). I was working for the DV8 / Snow Jam events from 1999 – 2002 as an announcer and as the BMX coordinator.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation at McGill on BMX culture in 2006. That’s why people see my name online as Dr. Wade Nelson.

I started running my own jams and contests in 1992. We did them in Richmond at the Skate Ranch initially. Then I took over the Nelson Contests in 1994 along with Rob Sigaty. I also did jams and events in Montreal when I lived there, and in Toronto, too. The most recent one was the reunion event in Nelson in August of 2022.

Denim on denim. 1986.

Denim on denim. 1986.

Justin: What was the Canadian freestyle BMX scene like in the late eighties and early nineties?

I was on the west side of the country. In the late 1980s, most people quit. The 1980s BMX trend had peaked. Those of us that did not quit bonded pretty tightly, as we were so few and so passionate. In 1988 in Vancouver, for me, the core crew was down to Alan Brand, Jason Brown and I, and then we met the Coquitlam folks – Greg Axford, Jamie McIntosh, and Shane Budnick. Then Darren Bolton. Other big names from slightly previously – Ron Mercer, Mel Gooder, Darren Wong, and others – we saw less for a while. Jay Miron moved out from Thunder Bay in 1990 for less than a year. We had a few different contest series – the NAFA ones and some put on by a gentleman named Ken Beattie from Vancouver Island. That was an excuse to get together and to take riding seriously enough to compete. We were mostly all flatlanders at the time – with the exception of Alan and Jay. By 1990, Jason Brown had a VHS video camera and we had a scene video (Canadians, Eh!). That brought us together.

We had friends from Alberta: Brent Oswald, Steve Roy, Darren Nordell, Don Tress, John Naicker, Al Mohr, Corey Bolton, Ryan McDowell, George, etc. They would make it to West Coast contests or to just come and hang out. Those folks knew people from Saskatchewan, and from Winnipeg, etc. It was a sociable network.

Some of us stopped riding flatland and started over as mini ramp riders and / or “street” riders after 1990. A few of us had Bully bashguards welded onto our frames.

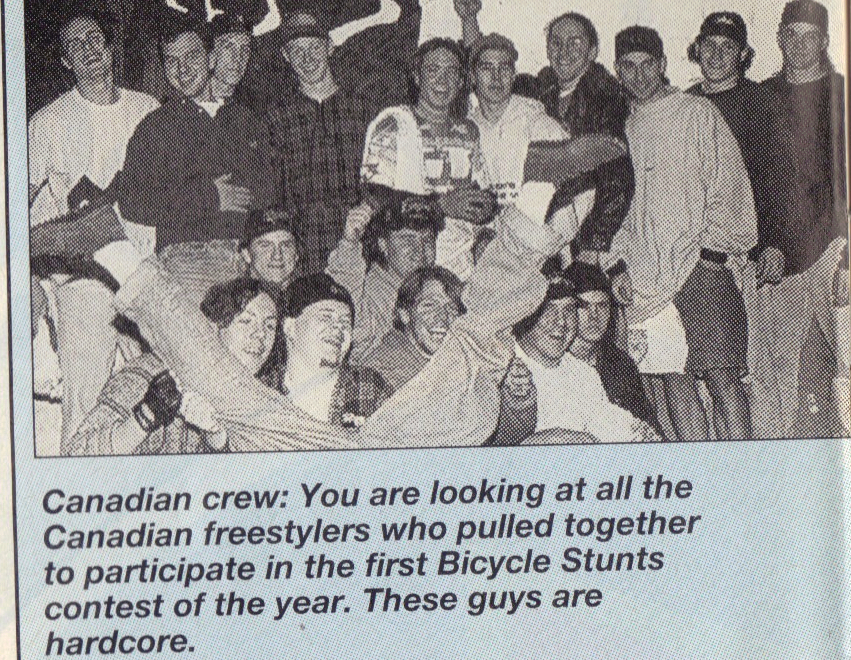

In 1992, a bunch of Canadians made it to the very first Mat Hoffman BS contest in Dallas, Texas. BMX Plus magazine ran a group picture of us. A lot of the names above are in that picture, along with a handful of Montreal riders (including Rick Maltais and Stephane Lavigne) that I would become friends with a couple years later when I moved to Montreal in 1994.

Texas BS Contest. 1992

Texas BS Contest. 1992

Aaron: What was Canadian BMX media like in those days? Who was making ‘zines, and was there much else going on in videos beyond the Canadians series?

I made a half-dozen or so issues of Wade ‘Zine in late 1989 – 1990 when I still lived in Vancouver. Ken Paul was doing Back Door out of Winnipeg. By the mid-90s, Ed Vandermolen was publishing Mob ‘Zine in the Toronto area. Brotharchy was out of Cranbrook, BC. Probably lots more. Yannick Dubois and JF Campeau made videos in Montreal – the Highroller series. Highrollers 5 was called Beer, Sex and BMX, and it was filmed in 1995. Highrollers 6 was called Journey. I don’t remember other videos being made in Eastern Canada in the first half of the 1990s, but I could of course be wrong. I can think of lots of regional scenes across the country, and I bet they at least put together clips of themselves to show in their own area. By the end of the 1990s and into the new century, there was the Flatland Manifesto and Vibe video series, and then there was Chase BMX Magazine from 1999 – 2003 and David Hawthorne’s RED BMX Magazine for a couple years after that. Canada was doing pretty well media-wise back then.

Justin: Can you talk more about your experience at the first two X Games? What was the atmosphere like and what were the highlights for you?

The first one in 1995 was called The Extreme Games, and none of us were sure what it would be. We didn’t trust it. We had gone through five to seven lean years. We trusted Mat Hoffman and his crew, but the Extreme Games seemed big, corporate, and suspect (even though the first one had some good folks helping run it for ESPN – Hal Brindley and Steve Buddendeck). The first one took place a week before a BS contest in Virginia Beach, so a group of us (Cecil Milligan, Greg Axford, Dave Osato, Rob Sigaty, Jamie McIntosh, Yannick Dubois and myself) jumped in a rental van in Montreal and hit both events, stopping to stay with Dave Mirra at the Superdome in Pennsylvania in between.

I talked my way into a Sport Climbing Judge pass at the first one and we abused this to the maximum. We weren’t used to rules and passes and things, and thus we had to subvert these (enthusiastically). I remember that Jay had fresh Schwinn stickers on his Hoffman prototype frame. I remember watching Vert. They had two separate vert ramps, I believe, and one wasn’t right so both skaters and BMXers used the same one. I remember watching Jay win the Dirt contest. Watching instant replay on giant TV screens was new. And I remember that the street course was not to be used by BMXers. Oh, and absolutely anybody could turn pro for inline in their first year.

For the second year, in 1996 – the first “X Games” – I remember talking my way into a “Crew” pass that could get me anywhere after explaining to the registration person that I was associated with GT Bicycles, and that I had delivered Rob Sigaty to the event for TM Woody Itson. It was sponsored by Nike, and people were trying to get the riders to cover the logos of other companies’ shoes. Uniforms had made a comeback. I remember the Dirt contest being at a different location than the Vert and Street contests. I remember sitting up in the VIP section all by myself watching the Street contest. I don’t remember the riding, but whenever anyone asks me if I know what contentment feels like, I think of that moment: I was warm in the sun, felt special, and was watching my favourite thing. I remember watching Vert with a whole bunch of Pros from other events in the section kept for the riders (the ESPN coverage has shots of me sitting beside Dennis McCoy as they wanted his reaction to Mirra, Hoffman, and Miron’s riding after he had concussed himself).

X Games TV screenshot of Wade and Dennis McCoy. 1996.

X Games TV screenshot of Wade and Dennis McCoy. 1996.

Justin: How do you think those early X Games events shaped BMX into what we know today?

This would be a 100,000 word essay. Briefly – it made things corporate and corporate-friendly. For better or worse. Less than ten years later, all the outsider companies had very little difficulty being a part of BMX Freestyle. 1990 – 1995, BMX was pretty punk rock. Afterward, it was less and less protective of the core. The core was no more? But if you weren’t riding until after the X Games, you wouldn’t even know. It’s like going from Fugazi to Limp Bizkit.

Aaron: Of all the riders who are still around from the pre-X Games era, whose riding has aged the best? Feel free to define that however you’d like.

I really don’t care about the riding “quality” anymore. It’s that someone still rides. It’s participation over performance. I think it’s particularly rad that some folks never did quit. I admire that. It is also rad that people came back to ride again. I am much less impressed by people who quit and then came back into it to collect but not ride.

If you are asking whose riding I still find aesthetically pleasing from back then – pre 1995 – I am still impressed by any Jay Miron footage from 1990 on. It’s an aggression thing with Jay. I love watching flatland footage of Steve Roy from back then. Steve’s riding embodies fun.

If one uses as a criterion of valuation, “influential” – it has to be Mat Hoffman and Kevin Jones. They weren’t the first, but almost everything can be traced back to these two. It really depends on which criteria one is emphasizing.

Justin: Can you talk more about your doctoral dissertation on BMX culture? What made you want to pursue that? What was the process of finding a professor to supervise that type of project?

It’s available online for anyone that wants to find it through McGill University. It’s called Reading Cycles: The Culture of BMX Freestyle. It’s close to 400 pages long with the pictures, but the online version is about 320 pages. Here is an abridged version of the abstract:

“This project serves two primary objectives: the examination of the figure of the BMX freestyle cycling Pro and the analysis of the role of the magazines within this particular culture or field in the construction and maintenance of this figure. Special-interest magazines are a part of a larger system and industries within which the ultimate goal is the sale of commodities. At the same time, they function as a site of credibility within a larger field, both conferring star status on particular individuals and approving particular commodities that are being offered to the readers. Special-interest magazines construct and sell audiences to advertisers, create star systems, propose candidates for stardom, help build image careers, contribute substantially to a “star currency” within the particular field, negotiate (i.e.; mediate) tensions between the advertisers, the stars, and the readers, help organize the time of a culture and work to infuse it with a sense of vitality through the punctual and ritualistic appearance of novel content, assist the consumer with their desires for commodities and stars by standing as catalogues of commodities (serving to educate newcomers in the protocol of the culture), provide new financial opportunities (such as the commodity form of the photo contingency), and in their complicity with the needs of those that provide their primary source of revenue, give more value to the advertising dollar in the construction of editorial content that could be seen as advertising.”

What happened is that Chase BMX Magazine was going to cease publication in the fall of 2003, and I was bummed about it when I went to see my supervisor. My plan was to do my dissertation on signature model commodities – and I had been doing research on guitars, specifically. He wasn’t really into it. I told him about the magazine ceasing publication after 19 issues, and that I had about 1000 BMX magazines going back to 1978. He got excited and we figured that I could do a BMX media project. So my number one procrastination became my homework.

Aaron: Chase served the purpose of growing the market for Ten Pack/Macneil – do you think it fell in to the archetype of the magazine/advertiser relationship you describe? Was there anything different about it that broke out of that traditional mold?

I was just chatting with Ken Paul, former editor of Chase, a few minutes ago (we are hoping to go see a Hives show together in November). My dissertation has a whole chapter on Chase. Jay Miron, Ken Paul, and the others involved genuinely wanted to do the magazine for the right reasons: To serve the culture and the riders. It wasn’t supposed to merely be an extension of World Bicycle Sports / Up North BMX Supply / Ten Pack Distribution / MacNeil Bikes / Metro Jams. The founders actually wanted to have the magazine connect the riders. That said, commercial media works to serve the industry. It gathers an audience to be sold to the advertisers. What is being produced is not content, it is audiences. When I am teaching, this is referred to as the “audience commodity” within discussions of political economy (that is, “watch the money”). What the founders wanted to have happen was that the other Canadian distributors would support the magazine through advertising. They did not do so, consistently. So, in the end, Chase seems like a catalogue for Ten Pack Distribution. But, again, remember that despite not getting support from the rest of the Canadian BMX industry in the form of paid advertisements, the Chase folks kept it going for nineteen issues over five years. It wasn’t good business. They did it, primarily, I believe, for the love of BMX.

Justin: How do you think BMX culture has changed in the period from 2006 when you completed your dissertation until now?

Clearly, digital media and modern social media use after the introduction of smartphones changed the world. Print magazines were dominant for decades, and then were displaced. The power of a few was spread out: diluted. More folks could create media and broadcast. This said, the core of the work in my dissertation still holds true. It is still about creating and maintaining an audience to sell to advertisers. The Pros still have to work with BMX media. They still have to maintain an image, a facade, and a constructed authenticity (which is an oxymoron / paradox).

Things are much much better, and much much worse. Both at the same time.

I use a phrase when teaching – the idea of being “complicit with your own exploitation.” I think this holds true. BMX Freestyle has always been beholden to business, but I think that it may be worse than ever in this regard. When the BMX business / industry is weak, the media and the culture in general (including the participants) has to bend to the needs of the advertisers. A strong BMX media would not have shaped what they do toward the needs of the advertisers so hard. But the sales are not strong, and the audiences constructed are not strong enough. So the editorial content of BMX media is often indistinguishable from advertising. I don’t begrudge folks for their complicitness – they have families to feed. The worst of this, perhaps, is that subsequent generations won’t know that there were once higher ideals. That editorial content should not be shaped by pressures from advertisers. But this is not just in the BMX world; this is a societal problem.

Aaron: In the current environment, media outlets have been quite open about catering content around their advertisers and that they are not producing journalism. Do you think this leaves an opening for others to produce something more central to the culture? Do you see anyone out there doing this now?

There is clearly a gap, and thus an opportunity. Again, I don’t think most people even know that there used to be “higher” ideals with regard to “journalism.” Young riders don’t know that they should want alternatives to what is available. It is beyond BMX, but society in general keeps people ignorant and consuming. People are complicit and are conforming to the needs of business. The riders’ goals, it seems to me, are to be sponsored and famous rather than to enjoy the non-business parts of the activity. Common sense, or rather the common sensibility, is the enemy.

As for folks filling the gaps at the moment – I will say this: I tend to follow folks and organizations that are trying to do it differently. Folks advocating for participation over performance. Advocating for women, queer folks, trans folks, folks with different physical abilities, folks talking openly about mental health….

Aaron: Some of the very first BMX blogs to exist were part of the Ronin website in the early 2000s, for which you wrote a few things. It was a pretty dominant format at its peak, but lacks the distribution qualities of social media. Can the format still be relevant? What value can it bring?

I wrote for Ronin for a while, yes. Shane Neville is an old friend. I can’t remember if I had my own blog page with them, but I think so. The problem now with blogs, especially if I am writing the posts – is that folks don’t want to read. I appreciate that you are publishing this and are letting me have such long answers, but folks aren’t going to have the patience to read this. Indeed, to be harsh, many folks today are functionally illiterate. I mean this as a combination of not being strong readers AND not having the attention span. My university students for the last four years have arrived from high school somewhat illiterate. Our modern culture—especially the use of smartphones and social media—is hobbling the young.

In late 2019, I did a 100-minute podcast with my friend Ant for his Harvester Bikes YouTube channel. It was his first podcast, and he had several thousand followers at the time. Three-and-a-half years later, it only has around 1,000 views. He has yet to post episode #2 and seems to have aborted the podcast project. Why didn’t his followers check it out? They don’t have the attention span, or the interest in listening to something educational about their favourite thing featuring an old guy. They can handle an unboxing video, or an all-jet-fuel build. Superficial, instant, disposable stuff. It’s a different moment in history, and many of the young folks would rather eat cotton candy over broccoli. One of his best customers has very popular social media accounts which have content that is somehow even lighter and hollower than cotton candy.

Yannick Dubois, Dave Mirra, and Wade. 1995.

Justin: Can you talk more about your job as a professor? Why did you pursue that career path? What is most rewarding about your job?

I taught my first university course at McGill 20 years ago (2003). I may have just taught my last courses in the Winter of 2023. You’ve caught me at a transitional time.

I had a mother that was very invested in me being “special.” Being “gifted.” She had me tested at 4 or 5 years old by a psychologist or someone who determined that I was already at a third-grade level for math and reading. So I was never not going to university when I was done high school.

I remember in 1989 thinking that I was going to have to quit riding because now life was going to get serious when I started at Simon Fraser University that fall. Quitting didn’t happen. I had worked my way up to 18 and over Expert for flatland by the end of 1989, and I definitely neglected my studies that first year. Sometime in 1990, maybe halfway, I turned Pro after having won the expert class five times. Finished the year out in second overall to Jason Brown, and then I was done with competitive flatland. I dove into my studies.

By 1993, I was done my 120 credits for university, but didn’t think that I was done with school. And I thought that I wanted to be a “TA” – a tutorial / teaching assistant – and these were grad students (Masters-level), so I moved to Montreal to attend Concordia. I Master-fied in 1997, and figured that I was done with school. My mom died in 1999, I freaked out a bit and regressed back to being a student to cope, starting a doctoral program at McGill.

When you have finished a Ph.D., you can be a professor. So I figured why not. It wasn’t a career choice or a passion as much as it was the next thing to do.

I don’t come from upper-class, educated people. I thought that being a professor was being a teacher who does some research. It turns out that one is supposed to be a researcher that has to do some teaching. Over the past sixteen years, I have focused on becoming the best teacher that I could be. To be more successful, I should have neglected my teaching and put about 80% into research and applying for grants.

Over the last several years, I have taught between five and nine classes per year. Teaching is my other happy place (other than riding and skateboarding at skateparks with friends). I am good at it. I can improv though classes because I know the material, and I am an excellent public speaker. I like to be the centre of attention. (There is a show-off component that I think that I picked up from 1980s Freestyle. It’s also why I placed so well in contests between 1988 – 1990 – I was charming. We used to get judged for showmanship, and the parents that served as judges loved me. My skills were okay, but I could entertain, and that was often the difference.) I think that my need to be the centre of attention and my ability to entertain my students while enlightening them is why I have been a popular professor.

Aaron: By “successful,” you mean by the standards of your field, right? Is there a path in that field to do things the way you want to do them and still feel satisfied professionally? In other words, is there a path to be successful on your terms?

By the standards of my field – academia – one could argue that I have been less than “successful.” But the field’s standards are not my standards. My criteria of valuation are different. I think that, especially now, what citizens need from universities is a primary commitment to teaching young folks and fostering their critical thinking skills. Much of what is wrong in the world, in my opinion, stems from the maintenance of an ignorant, disengaged, distracted, ill-informed population. This serves the status quo. The status quo does not like to be challenged, and mobilizes to repress such challenges. There are parallels here with calling out BMX media or the BMX industry, obviously. Satisfaction, to me, would be being able to be a professional contrarian, training others to think contrarily.

Justin: Before teaching, you had some jobs in the BMX industry. What were some memorable moments from that time? Were there any special projects you got to work on?

At the second X Games, I got introduced to an important person at Airwalk shoes. That person hired me to work at four B3 contests as an Airwalk rep. I got to work with Tony Hawk at one event as he was still sponsored by them in 1996. I made friends with my hero from the mid 1980s, Woody Itson, and got to be a substitute TM for GT Bicycles in 1997 for a couple contests – one in California, and one in Manhattan. I was the Rewind Clothing TM for a few years and got my friends clothes and photo contingencies. I was the BMX coordinator and MC for four years for the DV8 / Snow Jam tours across Canada and into the US. That was super fun, and it paid for graduate school. I worked for SST for Interbike between 1997 and 2002, and actually moved to California for six months to work for them (traveling to Taiwan for a month and China and Hong Kong for a week) in 2000. Not my idea or my work, but I did get to distribute gold-plated SST Orygs to friends back then.

Aaron: What keeps you still riding and involved in BMX at 50 years old?

Fifty-two, thank you very much. I have to ride. My friends that don’t are often quite miserable. About a dozen BMXers I know have taken their own lives. Not all for the same reasons, mind you, but I do wonder what if they could have turned the dial down from ten to two? I ride at about a two, and as such, I can get more sessions in for more years. It’s my happy place, my access to the purity and innocence of being twelve years old. Everything else that I have been involved in during my lifetime comes a distant second. Being a professor wasn’t nearly as satisfying as still being able to do nosepicks. I play guitar, but that isn’t a tenth as pleasurable. BMX is joy. Sunshine. Everything. Why would I stop that?

Justin: What was that process like of turning the dial down? How did you manage that transition mentally?

University got in the way first. My competitive streak, that drive for excellence, shut down around 1990 when the first Canadians Eh video came out and after I had been Pro for a while. The video had everything that I could do at the time in it, and I didn’t feel that I had to learn all new stuff. I had already peaked as a competitor. And one other thing – it hit me around this time that I was practicing rather than riding. The fun was not the priority anymore.

So I turned the dial down a bit. I started riding ramps more, and was back to being a novice. That was OK. I moved to Montreal to do my Masters degree, and maybe that turned the dial back a little. Then in 1995, the first big injury – I broke my tibia and fibula at my ankle and needed pins and plates. Another notch down on the dial. I separated my shoulder in 1998. I herniated two discs in my lower back in 1999. So, even dialed back to let’s say, seven of ten, wasn’t enough to be safe. In 2000 I started my doctoral program at McGill. Dial it back further. In 2004 I strained my knee for the first time. I had in mind that I would quit entirely if I ever hurt my knee. I was 33 by then, and was aware that mobility was precious. I even wrote a story for DIG Magazine about quitting at the time. Of course I couldn’t quit, but the dialing down continued. In 2010, I took the pegs and the front brakes off my bike after a major concussion at Woodward. Simplify. Just manuals and tailtaps for about seven years. By 2018, when I moved to Toronto for the second time, I had backed off to two of ten for a long time. I set up a bike with front brakes, a detangler and four pegs as I was going to be riding Joyride 150 a bunch. Drew Bezanson called me out for a nosepick over the spine, and I was back to front-wheel stunts again. Back to grinds. But, this time, at level 2. I was content with having merely shown up to ride and to competently do the basics. My attitude for the last five years is that I “win” by just having shown up. I am 52 years old and can still do much of what I could do 25 years ago. People seem genuinely happy to see me ride still, too.* So that’s something as well.

(*Darcy Saccucci and Greg Axford do not like to see me riding.)

Drew Bezanson and Wade.

Drew Bezanson and Wade.

Justin: Any final words or shout outs?

Thanks for the chance to broadcast my thoughts.

PS – Again – I am in transition. I might have something really big going on in the next year. Stay tuned.